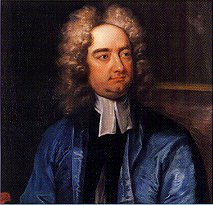

(1667 - 1745)

Jonathan Swift was born on November 30th 1667 in Dublin. His father died before he was born, and his nurse took him at the age of one year old to Whitehaven in Cumberland, where he remained with her until the age of 3. On his return to Ireland his education was paid for by his uncle, Godwin, first at Kilkenny School (1673) and then at Trinity College in Dublin (1682).After an undistinguished university career, he went to stay with his mother, Abigail Erick, in Leicester, and shortly afterwards, in 1689, he became secretary to Sir William Temple, the diplomat and writer, at Moor Park in Surrey, during which time he had full access to Temple’s impressive library. While he worked at Moor Park he paid a yearly visit to his mother, a journey of some 80 miles which he made on foot, and it was at Moor Park that he first met and tutored Esther Johnson, the eight year old daughter of Temple’s widowed sister's companion, who later appeared in his poetry as Stella, and became his lifelong companion. It was also here that he began his first major work, A Tale of a Tub, and completed The Battle of the Books, a satire concerning whether ancient or modern authors were to be preferred. Both works were published anonymously in 1704. He returned to Ireland in 1694, and was ordained as a priest in 1695. In 1696, he obtained a licence for non residence at his living in Kilroot, and rejoined Temple, beginning work on his patron’s memoirs and correspondence. When Temple died in 1699 Swift returned to Ireland once more, where, having resigned his living, he had hopes of becoming chaplain and secretary to the Earl of Berkeley, Lord Justice of Ireland, but he lost this opportunity because of an intrigue. He subsequently held various posts in the Irish Church, and in 1702 Stella, who had been left property in Ireland in Temple’s will, joined him in Dublin. In 1707 he was sent to London as an emissary of the Irish clergy, seeking remission of tax on Irish clerical incomes, but his suit was rejected by the Whig government.At this time he met Esther Vanhomrigh, who was to become the 'Vanessa' of his poetry. He then produced some pamphlets. On the fall of the Whig administration in 1710, he returned to London to renew his application for the remission of taxes on behalf of the Irish clergy with the new Tory government, and became editor of The Examiner.Between 1710 and 1713 he wrote detailed letters of his daily life to Esther Johnson which were later published as Letters to Stella. Important connections with the Tory administrationHe switched his allegiance from the Whigs (now labour party) to the Tories (now Conservative Party), and became deeply involved with the politics of the period, acting as a propagandist for the Tory administration of the Lords Bolingbrooke and Oxford. Particularly effective was his pamphlet The Conduct of the Allies, in which he accused Lord Marlborough of attempting to continue the war against France in order to make money.He received the reward for his services to the Tory government in 1713 in the form of the Deanery of St Patrick's Cathedral in Dublin, a position he held until the end of his life, though at this point he was disappointed, regarding it as an exile.In 1714, he became a founder member of the Scriblerus Club, whose other members included Pope, Gay, Arbuthnot and Congreve, but on the death of Queen Anne in the same year the Tory administration was pushed from office, and he left once again for Ireland.Vanessa follows him to Ireland. Esther Vanhomrighe, whose mother had died and who had property in Ireland, followed him, living at Cellbridge, a few miles from Dublin. From 1719, he wrote a series of poems to Stella, usually on the occasion of her birthday. In 1723, Esther Vanhomrighe died, having cancelled a will in favour of Swift just before. He wrote more pamphlets which won him great popularity in Dublin. He probably began writing Gullivers’ Travels in 1721, finishing the work in 1725. When published anonymously in 1726 it was an immediate success. In the same year he stayed with Alexander Pope in Twickenham, and between 1727 and 1736 five volumes of Swift-Pope Miscellanies were published.Much to his grief, Stella died in 1728 and he was too ill to attend the funeral. Afterwards, a lock of her hair was found in his desk, wrapped in a paper bearing the words, 'Only a woman’s hair'. More pamphlets and his popularity in Ireland continued and in the same year he received the freedom of Dublin.He lived frugally, and reputedly spent a third of his income on charities, saving what he could to contribute to the founding of St. Patrick's Hospital, a charitable institution for the care of idiots and the insane (of which he felt Ireland was much in need), which opened in 1757. He gradually lost his faculties and his mental decay, which he had always feared, became pronounced from 1738. Paralysis was followed by aphasia and a long period of apathy. He died on October 19th 1745, and was buried in St Patrick’s, alongside Stella. He wrote his own epitaph : ‘The body of Jonathan Swift, Doctor of Sacred Theology, Dean of this Cathedral Church, is buried here, where fierce indignation can no more lacerate his heart. Go, traveller, and imitate, if you can, one who strove with all his strength to champion liberty.’

My selection:

Gulliver's Travels : (Les Voyages de Gulliver) 1726 (amended in 1735)

A satire in the form of a narrative of travels. Much more than children's book, it is a vicious satire of human foibles and 18th century British politics. Published in his sixtieth year, Gulliver’s Travels is the most famous example of Jonathan Swift’s satirical works and was the only one he received payment for (£200) since most of his works were vehemently and dangerously political, and were published anonymously or under one of his many pen-names. Although Swift seems to have been writing the book from 1720 onwards, it was only completed and published in 1726. Lemuel Gulliver, a ship’s surgeon, tells the story of his shipwreck on the island of Lilliput. Here people are six inches rather than six feet tall and as such their actions, debates and pageantry seem utterly ridiculous. Their fatuous political arguments (should an egg be broken at the big or small end?) mock the English political and religious debates of Swift’s time. On his ‘travels’, Gulliver meets various other strange humanoids: the extremely tall people of Brobdingnag and later the useless scientists and philosophers of Laputa and Lagado who spend their time trying to extract sunshine from cucumbers while failing to do anything worthwhile. Glubbdubdrib and Luggnagg present Gulliver with more intriguing insights still. In the final section of the book, Gulliver meets the Houyhnhnms who are horses empowered with reason, simplicity and dignity and the Yahoos who look like humans but live revolting lives of vice and brutality. Gulliver and the reader get to see the human race through a series of curved mirrors therefore and return to the real world somewhat disgusted. However, despite its dark themes, the book was an immediate success and has remained a favourite with adults who enjoy the satire and children who like the adventuring (or perhaps it is the other way around).