The Domesday Book is one of the most famous historical records held by The National Archives. It was written over nine hundred years ago under the orders of King William the Conqueror. William wanted to know how much his kingdom was worth and how much taxation he could command. The result is a detailed survey of the land held by the king and his people.

Domesday is the most famous and earliest surviving public record.

It is a highly detailed survey and valuation of all the land held by the King and his chief tenants, along with all the resources that went with the land in late 11th century England.

The survey was a massive enterprise, and the record of that survey, Domesday Book, was a remarkable achievement It was produced at amazing speed in the years after the Conquest .

There is nothing like it in England until the censuses of the 19th century.

Historical context:

In 1066 William Duke of Normandy defeated the Anglo-Saxon King, Harold II, at the Battle of Hastings and became King of England. In 1085 England was again threatened with invasion, this time from Denmark. William had to pay for the mercenary army he hired to defend his kingdom. To do this he needed to know what financial and military resources were available to him.

At Christmas 1085, he made a survey to discover the resources and taxable values of all the boroughs and manors in England. He wanted to discover who owned what, how much it was worth and how much was owed to him as King in tax, rents, and military service.

A reassessment of the tax known as the geld took place at about the same time as Domesday and still survives for the south west. But Domesday is much more than just a tax record. It also records which manors belonged to which estates and gives the identities of the King’s tenants-in-chief who owed him military service in the form of knights to fight in his army. The King was essentially interested in tracing, recording and recovering his royal rights and revenues which he wished to maximise.

It was also in the interests of his chief barons to co-operate in the survey since it set on permanent record the tenurial gains they had made since 1066. Recent research has suggested that William only commissioned the survey in 1085 and never intended the results to be written up into a book. Some say that it was his son and successor, William Rufus, who ordered the production of Domesday Book itself.

Why is it called ‘Domesday’?

The nickname ‘Domesday’ may refer to the Biblical Day of Judgement, or ‘doomsday’ when Christ will return to judge the living and the dead. Just as there will be no appeal on that day against his decisions, so Domesday Book has the final word – there is no appeal beyond it as evidence of legal title to land. For many centuries Domesday was regarded as the authoritative register regarding rightful possession and was used mainly for that purpose. It was called Domesday by 1180. Before that it was known as the Winchester Roll or King’s Roll, and sometimes as the Book of the Treasury.

How many books make up the whole of the Domesday survey?

The Domesday Book is really two independent works. One, known as Little Domesday, covers Norfolk, Suffolk and Essex. The other, Great Domesday, covers the rest of England, except for lands in the north that would later become Westmorland, Cumberland, Northumberland and County Durham (because some of these lands were under Scottish control at the time). There are also no surveys of London, Winchester and some other towns. The omission of these two major cities is probably due to their size and complexity. Most of Cumberland and Westmorland are missing because they were not conquered until some time after the survey.

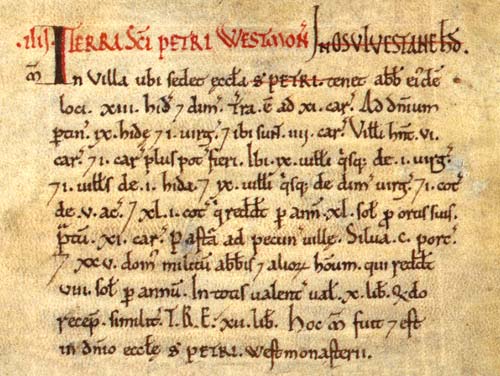

The main volume, Great Domesday, is written on sheep-skin parchment using black and red ink only (red used for the county titles atop each page, and corrections and alterations).

How was the information collected?

Royal commissioners were sent out around England to collect and record the information from thousands of settlements; the country was split up into 7 regions, or 'circuits' of the country, with 3 or 4 commissioners being assigned to each. They carried with them a set of questions and put these to a jury of representatives - made up of barons and villagers alike - from each county. They wrote down all of the information in Latin, as with the final Domesday document itself. Once they returned to London the information was combined with earlier records, from both before and after the Conquest, and was then, circuit by circuit, entered into the final Domesday Book.

Why is the Domesday Book still important today?

The Domesday Book provides an invaluable insight into the economy and society of 11th century Norman England. For historians it can be used, amongst other things, to discover the wealth of England at the time, information about the feudal system existent in society (the social hierarchy from the king down to villagers and slaves), and information about the geography and demographic situation of the country. For local historians it can reveal the history of a local settlement and its population and surroundings, whilst for genealogists it provides a useful and fascinating resource for tracing family lines. Through the centuries the Domesday Book has also been used as evidence in disputes over ancient land and property rights, though the last case of this was in the 1960s.

Where can I see the Domesday Book?

Containing 413 pages, it is currently housed in a specially made chest at London's Public Record Office in Kew, London. Indeed, the original Domesday Book is deemed too valuable and fragile to be exhibited in public and so is kept in private at the National Archives - formerly the Public Records Office - in Kew, London (though it is still used on occasions by students and academics interested in its study). A copy of the document has been made and can be seen in a special exhibition area at the National Archives. For details of how and when to visit see the National Archives website.