Magna Carta, which means ‘The Great Charter’, is one of the most famous documents in the world. In fact the whole document is in Latin. It was issued by King John of England who reigned from 1199 until 1216 as a practical solution to the political crisis he faced in 1215.

The Magna Carta established for the first time the principle that everybody, including the king, was subject to the law.

Although nearly a third of the text was deleted or substantially rewritten within ten years, and almost all the clauses have been repealed in modern times, Magna Carta remains a cornerstone of the British constitution.

On June 15th, 1215, in a field at Runnymede, King John affixed his seal to Magna Carta. Confronted by 40 rebellious barons, he consented to their demands in order to avoid civil war.

On 19th June 1215 the rebel barons made their formal peace with King John and renewed their oaths of allegiance to him.

The King’s clerks set about drawing up copies of the agreement for distribution throughout the kingdom.

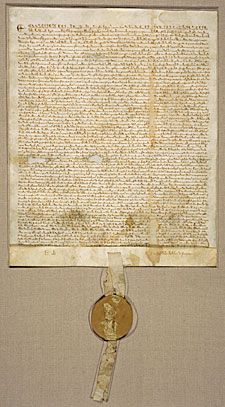

It is not certain how many copies of the 1215 Magna Carta were originally issued, but four copies still survive: one in Lincoln Cathedral; one in Salisbury Cathedral; and two at the British Library. Like other medieval royal charters, Magna Carta was authenticated with the Great Seal, not by the signature of the king.

Just 10 weeks later, Pope Innocent III nullified the agreement, and England plunged into internal war.

Although Magna Carta failed to resolve the conflict between King John and his barons, it was reissued several times after his death. The 1225 version of Magna Carta, freely issued by Henry III (reigned 1216-72) in return for a tax granted to him by the whole kingdom, took this idea further and became the definitive version of the text. Three clauses of the 1225 Magna Carta remain on the statute book today. Although most of the clauses of Magna Carta have now been repealed, the many divergent uses that have been made of it since the Middle Ages have shaped its meaning in the modern era, and it has become a potent, international rallying cry against the arbitrary use of power.

Most of the 63 clauses granted by King John dealt with specific grievances relating to his rule. However, buried within them were a number of fundamental values that both challenged the autocracy of the king and proved highly adaptable in future centuries. Most famously, the 39th clause gave all ‘free men’ the right to justice and a fair trial. Some of Magna Carta’s core principles are echoed in the United States Bill of Rights (1791) and in many other constitutional documents around the world, as well as in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and the European Convention on Human Rights (1950).

In 1265 - just 40 years after Henry III's final reissuing of Magna Carta - the relationship between the promises made by the king and the granting of taxation paved the way for the first English Parliament.

In the next century, Parliament interpreted Magna Carta as a right to a fair trial for all subjects.

During the Stuart period, and particularly in the English Civil War, Magna Carta was used to restrain the power of monarchs (at a time when monarchs on the continent were supremely powerful).

There are strong influences from Magna Carta in the American Bill of Rights (written in 1791). To this day there is a 1297 copy in the National Archives in Washington DC.

Even more recently, we can see the basic principles of Magna Carta very clearly in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights - penned in 1948 just after the Second World War.

When King John stuck his seal on that parchment eight centuries ago, he could not possibly have known the magnitude of what he was doing.

Magna Carta was written by a group of 13th-century barons to protect their rights and property against a tyrannical king. It is concerned with many practical matters and specific grievances relevant to the feudal system under which they lived. The interests of the common man were hardly apparent in the minds of the men who brokered the agreement. But there are two principles expressed in Magna Carta that resonate to this day:

"No freeman shall be taken, imprisoned, disseised, outlawed, banished, or in any way destroyed, nor will We proceed against or prosecute him, except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land."

"To no one will We sell, to no one will We deny or delay, right or justice."

During the American Revolution, Magna Carta served to inspire and justify action in liberty’s defense. The colonists believed they were entitled to the same rights as Englishmen, rights guaranteed in Magna Carta. They embedded those rights into the laws of their states and later into the Constitution and Bill of Rights.

The Fifth Amendment to the Constitution ("no person shall . . . be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.") is a direct descendent of Magna Carta's guarantee of proceedings according to the "law of the land."

Here you can find a translation of the text. Magna Carta Translation.