The present state of Massachusetts was explored in the late 16th and early 17th centuries but was not permanently settled until the Pilgrims settled at Plymouth in 1620. These first permanent settlers were not fortune hunters but a religious group, whose first landfall was Cape Cod rather than their original Virginia destination. In December 1620 they landed at Plymouth, where they established a colony according to terms drawn up in the Mayflower Compact before debarking.

The Pilgrims were English Separatists. In the first years of the 17th century, small numbers of English Puritans broke away from the Church of England because they felt that it had not completed the work of the Reformation. They committed themselves to a life based on the Bible.

Most of these Separatists were farmers, poorly educated and without social or political standing. One of the Separatist congregations was led by William Brewster and the Rev. Richard Clifton in the village of Scrooby in Nottinghamshire. The Scrooby group immigrated to Amsterdam in 1608 to escape harassment and religious persecution. The next year they moved to Leiden, in Holland where, enjoying full religious freedom, they remained for almost 12 years.

In 1617, discouraged by economic difficulties, the pervasive Dutch influence on their children, and their inability to secure civil autonomy, the congregation voted to immigrate to America. Unable to finance the costs of the emigration with their own meagre resources, they negotiated a financial agreement with Thomas Weston, a prominent London iron merchant. Fewer than half of the group's members elected to leave Leiden. A small ship, the Speedwell, carried them to Southampton, England, where they were to join another group of Separatists and pick up a second ship.

After some delays and disputes, the voyagers regrouped at Plymouth aboard the 180-ton Mayflower. It began its historic voyage on September 16th, 1620, with about 102 passengers.

After a 65-day journey, the Pilgrims sighted Cape Cod on November 19th. Unable to reach the land they had contracted for, they anchored (November 21st) at the site of Provincetown. Because they had no legal right to settle in the region, they drew up the Mayflower Compact, creating their own government. The settlers soon discovered Plymouth Harbour, on the western side of Cape Cod Bay and made their historic landing on December 21st; the main body of settlers followed on December 26th.

The English ship the Mayflower (a merchant ship that had originally been constructed for transporting wine) carried the Separatist Puritans Pilgrims, to Plymouth. The Mayflower carried 102 passengers, only 37 of whom were from the Leiden congregation, in addition to the crew. The voyage took 65 days, during which two persons died.

A boy, Oceanus Hopkins (son of Stephen Hopkins), was born at sea, and another, Peregrine White, was born as the ship lay at anchor off Cape Cod. The ship came in sight of Cape Cod on November 19th and sailed south. The colonists had been granted territory in Virginia but probably headed for a planned destination near the mouth of the Hudson River. The Mayflower turned back, however, and dropped anchor at Provincetown on November 21st.

That day 41 men signed the so-called Mayflower Compact, a "plantation covenant" modelled after a Separatist church covenant, by which they agreed to establish a "Civil Body Politic" (a temporary government) and to be bound by its laws. This agreement was thought necessary because there were rumours that some of the non-Separatists, called "Strangers," among the passengers would defy the Pilgrims if they landed in a place other than that specified in the land grant they had received from the London Company. The compact became the basis of government in the Plymouth Colony. After it was signed, the Pilgrims elected John Carver their first governor, with Stephen Hopkins as Assistant governor.

After weeks of scouting for a suitable settlement area, the Mayflower's passengers finally landed at Plymouth on December 26th, 1620. Although the Mayflower's captain and part-owner, Christopher Jones, had threatened to leave the Pilgrims unless they quickly found a place to land, the ship remained at Plymouth during the first terrible winter of 1620-21, when half of the colonists died.

To finance their journey and settlement the Pilgrims had organized a joint-stock venture. Capital was provided by a group of London businessmen who expected - erroneously - to profit from the colony. During the first winter, more than half of the settlers died, as a result of poor nutrition and inadequate housing, but the colony survived due in part to the able leadership of John Carver, William Bradford, William Brewster, Edward Winslow, and Myles Standish.

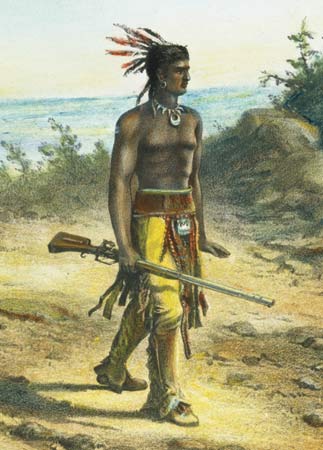

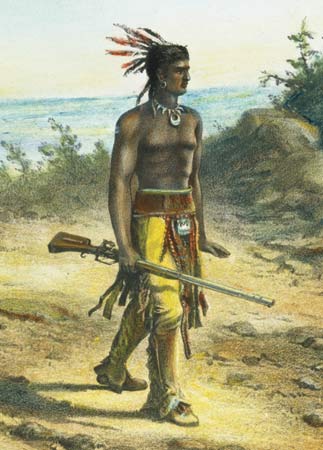

Squanto, a local Indian, taught the Pilgrims how to plant corn and where to fish and trap beaver. Without good harbours or extensive tracts of fertile land, however, Plymouth became a colony of subsistence farming on small private holdings once the original communal labour system was ended in 1623.

The Pilgrims were soon followed by other English settlers. Puritanism was the political force in the Bay Colony, whose leaders sought to establish a Bible commonwealth. Citizenship (called freeman ship) was restricted (until 1664) to church members. Religious dissenters were banished from the colony.

Within the framework of religious restriction, however, the colony early developed representative institutions. In 1632 the freemen gained the right to elect the governor directly, and in 1634 the freemen of each town won the right to send deputies to the General Court.

Throughout this early period new immigrants arrived, settling along the coast and a short distance inland. Farming, lumbering, and fishing were the principal occupations. Movement into the interior brought conflict with the Indians, as in The Pequot War (1637). In 1643 the Bay Colony formed the New England Confederation with Plymouth, Connecticut, and New Haven colonies to coordinate defence. Continual disagreements arose between the colonists and the English government, especially after the restoration of the English monarchy in 1660.

Finally, in 1684 the colony's charter was revoked, and in 1686 the Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth colonies were included in the Dominion of New England under Sir Edmund Andros. News of the Glorious Revolution in England prompted uprisings against Andros and the dissolution of the Dominion in 1689. Two years later a royal charter was issued that incorporated Plymouth Colony and the Province of Maine within Massachusetts but placed the extended colony under a royal governor and removed the religious qualification for voting. The authority of the Puritan clergy, already much weakened, was further diminished as a result of the Salem Witch Trials of 1692. The clergy were blamed for fanning the hysteria that led to the execution of 20 people.

Plymouth's government was initially vested in a body of freemen who met in an annual General Court to elect the governor and assistants, enact laws, and levy taxes. By 1639, however, expansion of the colony necessitated replacing the yearly assembly of freemen with a representative body of deputies elected annually by the seven towns. The governor and his assistants, still elected annually by the freemen, had no veto. At first, ownership of property was not required for voting, but freeman ship was restricted to adult Protestant males of good character. Quakers were denied the ballot in 1659; church membership was required for freemen in 1668 and, a year later, the ownership of a small amount of property as well.

Plymouth was made part of the Dominion of New England in 1686. When the Dominion was overthrown (1689), Plymouth re-established its government, but in 1691 it was joined to the much more populous and prosperous colony of Massachusetts Bay to form the royal province of Massachusetts. At the time Plymouth Colony had between 7,000 and 7,500 inhabitants.