Millions of Americans have made the United States the most multicultural nation in the world.

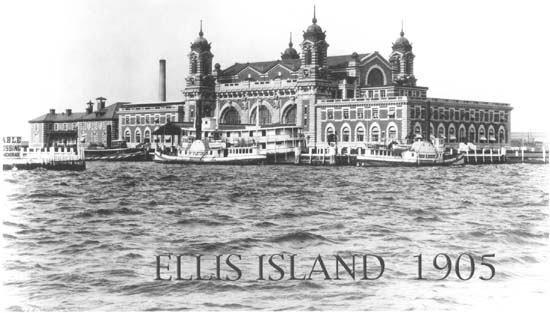

From the time Ellis Island opened in upper New York Harbour near the Statue of Liberty in 1892 to the time it closed in 1954, it served as the gateway for the vast majority of new immigrants.

THE JOURNEY :

Immigrants sailed to America in hopes of carving out new destinies for themselves. Most were fleeing religious persecution, political oppression and economic hardship. Thousands of people arrived daily in New York Harbour on steamships from mostly eastern and southern Europe. The first - and second - class passengers were allowed to pass inspection aboard ship and go directly ashore. Only steerage passengers had to take the ferry to Ellis Island for inspection. However, for all of them the trip meant days and sometimes months aboard overcrowded ships often travelling through hazardous weather. Substandard food and sanitation conditions only compounded the misery for many who had become sick aboard these ships. Nevertheless, the promise of freedom and opportunity made even the most arduous trip worth it. The opening of Ellis Island began a new era of restriction in the history of immigration. Here, the inspectors determined each newcomer’s eligibility to land according to United States law. For the vast majority of immigrants, Ellis Island meant three to five hours of waiting for a brief medical and legal examination. For others, it meant a longer stay with additional testing or a legal hearing. For an unfortunate two percent, it meant exclusion and a return trip to the homeland.

ARRIVAL :

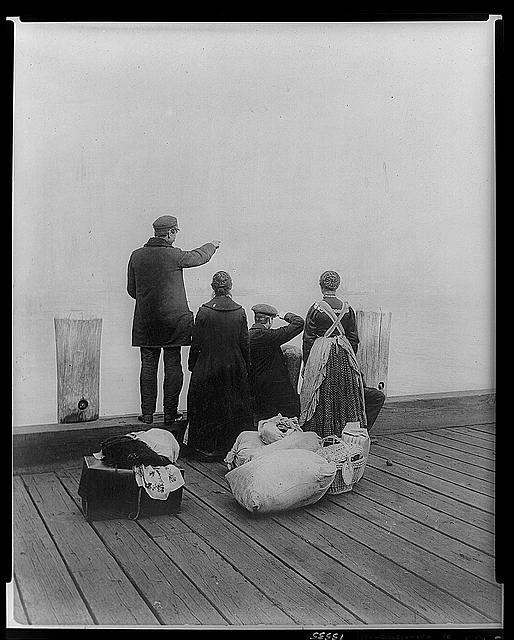

Immigrant arrivals reached approximately one million each year during the peak immigration period - 1900-1914. The ever-growing numbers taxed the facility with long lines and overcrowding. Ships dropped anchor outside the Narrows, where quarantine officers would come aboard to check for signs of epidemic diseases. If a ship was free of disease, doctors would then examine the first and second-class passengers, most of whom were given permission to land as soon as the ship docked. Steerage-class passengers were ferried to Ellis Island for inspection. Sometimes new arrivals had to wait aboard their ships for days before being transferred to Ellis Island. Once there, they were often confined to the overcrowded barges for hours without food or water, waiting for their turn to disembark for inspection. The barges, chartered by the steamship lines, lacked adequate toilets and lifesaving equipment; they were freezing cold in winter and unbearably hot in the summer. When disembarking at Ellis Island, some immigrants were so encumbered with large bundles that they kept their health certificates handy by clenching them between their teeth. Their assortment of baggage contained what must have been their most prized but portable belongings: clothing, feather beds, dinnerware, as well as photographs, family prayer books and other mementos of the homeland.

MENTAL INSPECTION :

According to a 1917 U.S. Public Health Service manual, 9 out of 100 immigrants were marked with an “X” during the line inspection and were sent to mental examination rooms for further questioning. During this primary examination, doctors first asked the immigrants to answer a few questions about themselves and then to solve simple arithmetic problems or count backward from 20 to 1 or complete a puzzle. Out of the nine immigrants held for this “weeding out” session, perhaps one or two would be detained for a secondary session of more extensive testing.

LEGAL INSPECTION :

After the medical inspection, each immigrant filed up to the inspector’s desk at the far end of the Registry Room for his or her legal examination, an experience that was often compared to the Day of Judgment. To determine an immigrant’s social, economic and moral fitness, inspectors asked a rapid-fire series of questions, such as: Are you married or single? What is your occupation? How much money do you have? Have you ever been convicted of a crime? The interrogation was over in a matter of minutes, after which an immigrant was either permitted to enter the United States or detained for a legal hearing.

LITERACY TEST :

Anti-immigration forces had been trying to impose a literacy test since the 1880s as a means of restricting immigration. They finally succeeded with the Immigration Act of 1917, passed over President Woodrow Wilson’s veto. This law required all immigrants 16 years or older to read a 40-word passage in their native language. These dual-language cards were used by inspectors to test immigrants’ literacy.

LIABLE TO BECOME A PUBLIC CHARGE :

Any immigrant deemed “liable to become a public charge” was denied entry to the United states. To Ellis Island inspectors, this clause, which has been a cornerstone of immigration policy since 1882, meant those who appeared unable to support themselves and, therefore, likely to become a burden on society. Ellis Island inspectors carefully weighed the prospects of new arrivals, especially those of women and children intending to rejoin husbands and fathers in this country. Immigrants had to show their money to prove they were not paupers. The amount was left to the discretion of the inspector until 1909 when Commissioner of Immigration William Williams directed that all immigrants must have railroad tickets to their destinations and at least $25 — at that time, the approximate equivalent of an inspector’s salary. Within a few months, Williams was forced to withdraw his order because of pressure from immigrant aid societies.

WOMEN AND CHILDREN :

Women and children were detained until their safety, after they left Ellis Island, was assured. A telegram, letter or prepaid ticket from waiting relatives was usually required before the detained women and children could be sent on their way. Single women were not allowed to leave Ellis Island with a man who was not related to them. When a fiancé and his intended were reunited at Ellis Island, their marriage was often performed right on the island - then they were free to leave.

FREE TO LAND :

After being inspected and receiving permission to leave the island, immigrants could make travel arrangements to their final destinations, get something to eat and exchange their money for American dollars. Relatives and friends who came to Ellis Island for joyous reunions (often after years of separation) could escort the immigrants to their new homes. Immigrants boarded ferries to New York and New Jersey and, at last, were free to land in America. Only one third of the immigrants who came to the United States through Ellis Island stayed in New York City. The majority scattered to all points across the country via a railroad that crisscrossed the entire continent and offered easy access to all of America's major cities. After immigrants had arranged their travel plans they were given tags to pin to their hats or coats. The tags showed the railroad conductors what lines the immigrants were travelling and what connections to make to reach their destinations.