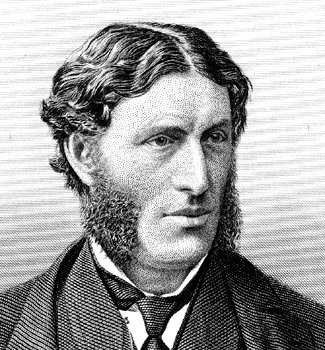

MATTHEW ARNOLD (1822-1888) was an English poet and cultural critic who worked as an inspector of schools.

Matthew Arnold has been characterized as a sage writer, a type of writer who chastises and instructs the reader on contemporary social issues.

Although remembered now for his elegantly argued critical essays, Matthew Arnold began his career as a poet, winning early recognition as a student at the Rugby School where his father, Thomas Arnold, had earned national acclaim as a strict and innovative headmaster.

In 1857 he was offered a position, which he accepted and held until 1867, as Professor of Poetry at Oxford. Arnold became the first professor to lecture in English rather than Latin.

DOVER BEACH

The sea is calm to-night.

The tide is full, the moon lies fair

Upon the straits; on the French coast the light

Gleams and is gone; the cliffs of England stand;

Glimmering and vast, out in the tranquil bay.

Come to the window, sweet is the night-air!

Only, from the long line of spray

Where the sea meets the moon-blanched land,

Listen! you hear the grating roar

Of pebbles which the waves draw back, and fling,

At their return, up the high strand,

Begin, and cease, and then again begin,

With tremulous cadence slow, and bring

The eternal note of sadness in.

Sophocles long ago

Heard it on the A gaean, and it brought

Into his mind the turbid ebb and flow

Of human misery; we

Find also in the sound a thought,

Hearing it by this distant northern sea.

The Sea of Faith

Was once, too, at the full, and round earth's shore

Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furled.

But now I only hear

Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar,

Retreating, to the breath

Of the night-wind, down the vast edges drear

And naked shingles of the world.

Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

LONGING

Come to me in my dreams, and then

By day I shall be well again!

For so the night will more than pay

The hopeless longing of the day.

Come, as thou cam'st a thousand times,

A messenger from radiant climes,

And smile on thy new world, and be

As kind to others as to me!

Or, as thou never cam'st in sooth,

Come now, and let me dream it truth,

And part my hair, and kiss my brow,

And say, My love why sufferest thou?

Come to me in my dreams, and then

By day I shall be well again!

For so the night will more than pay

The hopeless longing of the day.

GROWING OLD

What is it to grow old?

Is it to lose the glory of the form,

The lustre of the eye?

Is it for beauty to forego her wreath?

Yes, but not for this alone.

Is it to feel our strength -

Not our bloom only, but our strength -decay?

Is it to feel each limb

Grow stiffer, every function less exact,

Each nerve more weakly strung?

Yes, this, and more! but not,

Ah, 'tis not what in youth we dreamed 'twould be!

'Tis not to have our life

Mellowed and softened as with sunset-glow,

A golden day's decline!

'Tis not to see the world

As from a height, with rapt prophetic eyes,

And heart profoundly stirred;

And weep, and feel the fulness of the past,

The years that are no more!

It is to spend long days

And not once feel that we were ever young.

It is to add, immured

In the hot prison of the present, month

To month with weary pain.

It is to suffer this,

And feel but half, and feebly, what we feel:

Deep in our hidden heart

Festers the dull remembrance of a change,

But no emotion -none.

It is -last stage of all -

When we are frozen up within, and quite

The phantom of ourselves,

To hear the world applaud the hollow ghost

Which blamed the living man.