Many people assume that, as a direct result of women’s war work during the First World War, they were given the vote on equal terms to men. However, they were not.

The move for women to have the vote started in 1897 when Millicent Fawcett founded the National Union of Women’s Suffrage. She believed in peaceful protest. She felt that any violence or trouble would persuade men that women could not be trusted to have the right to vote. Her game plan was patience and logical arguments. Fawcett argued that women could hold responsible posts in society such as sitting on school boards – but could not be trusted to vote; she argued that if parliament made laws and if women had to obey those laws, then women should be part of the process of making those laws.

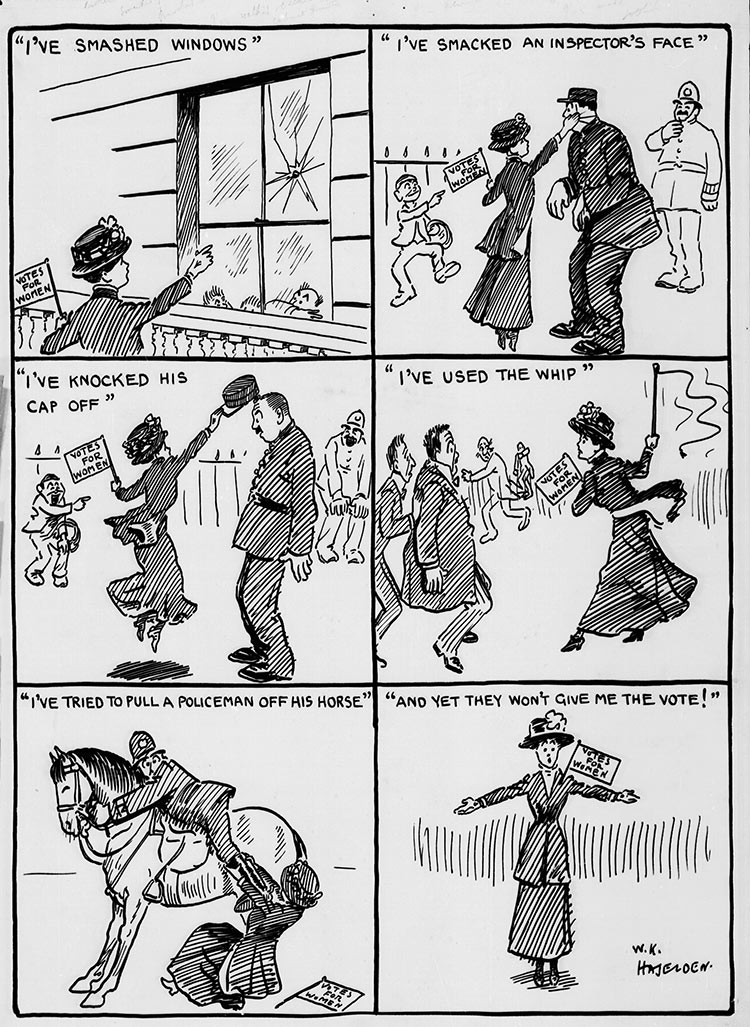

However, Fawcett’s progress was very slow. She converted some of the members of the Labour Representation Committee (soon to be the Labour Party) but most men in Parliament believed that women simply would not understand how Parliament worked and therefore should not take part in the electoral process. This left many women angry and in 1903 the Women’s Social and Political Union was founded by Emmeline Pankhurst and her two daughters Christabel and Sylvia. The Union became known as the Suffragettes. They were prepared to use violence to get what they wanted. They burned down churches as the Church of England was against what they wanted; they vandalised Oxford Street; they chained themselves to Buckingham Palace as the Royal Family were seen to be against women having the right to vote. Politicians were attacked as they went to work. Their homes were fire bombed.

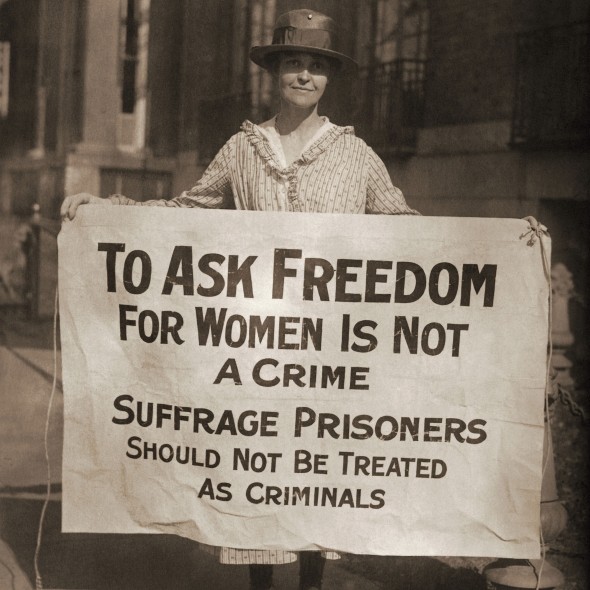

Suffragettes were quite happy to go to prison. They went on hunger strikes. The government was very concerned that they might die in prison thus giving the movement martyrs. Prison governors were ordered to force feed Suffragettes.

The government of Asquith responded with the Cat and Mouse Act. When a Suffragette was sent to prison, it was assumed that she would go on hunger strike as this caused the authorities maximum discomfort. The Cat and Mouse Act allowed the Suffragettes to go on a hunger strike and let them get weaker and weaker. Force feeding was not used. When the Suffragettes were very weak, they were released from prison. Those who were released were so weak that they could take no part in violent Suffragette struggles. When those who had been arrested and released had regained their strength, they were re-arrested for the most trivial of reason and the whole process started again. This, from the government’s point of view, was a very simple but effective weapon.

As a result, the Suffragettes became more extreme. The most famous act associated with the Suffragettes was at the June 1913 Derby when Emily Wilding Davison threw herself under the King’s horse, Anmer. She was killed and the Suffragettes had their first martyr. However, her actions probably did more harm than good to the cause as she was a highly educated woman. Many men asked the simple question – if this is what an educated woman does, what might a less educated woman do? How can they possibly be given the right to vote?

The Suffragettes became even more violent. In February 1913 they blew up part of David Lloyd George’s house – he was probably Britain’s most famous politician at this time and he was thought to be a supporter of the right for women to have the vote!

However, Britain and Europe was plunged into World War One in August 1914. In a display of patriotism, Emmeline Pankhurst instructed the Suffragettes to stop their campaign of violence and support in every way the government and its war effort. The work done by women in the First World War was to be vital for Britain’s war effort. In 1918, the Representation of the People Act was passed by Parliament and women were given limited voting rights. (women over 30 could vote but only if they met minimum property qualifications or were married to a man who did.) This act was the first to include practically all men in the political system and began the inclusion of women, extending the franchise by 5.6 million men and 8.4 million women.Women were not given the vote on the same terms as men until a decade after the act was passed: on 2nd July 1928, the Second Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act was passed into law.

In a cruel twist of fate, Emmeline Pankhurst, leader of the militant WSPU, died on 14th June 1928, some 18 days before equal suffrage rights were granted.